Liquidus vs. Solidus

Simply put, liquidus is the lowest temperature at which an alloy is completely liquid; solidus is the highest temperature at which an alloy is completely solid.

Pure metals are fluid, and they melt at a single temperature. For example, silver melts at 1761°F (961°C), and copper melts at 1981°F (1083°C). However, alloys containing varying percentages of silver and copper will not have a single melting temperature, but rather a melting temperature range. Since most brazing filler metals are alloys, you will be dealing with melting temperature ranges as you select materials.

The exception is a class of alloys called eutectics. Although these are not pure metals, they do have a single melting point, because the melting point, or solidus, and flow point, or liquidus, are identical. For example, Lucas-Milhaupt Silvaloy 720/721 melts and flows at 1435°F (780°C).

Brazing Considerations

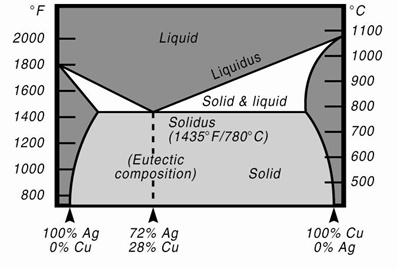

Figure 1 is a phase diagram for the silver-copper binary system. Note that, at the 72% silver, 28% copper composition, liquidus and solidus temperatures are the same. The alloys to the left or right of this eutectic composition do not change directly from solid to liquid, but pass through a "mushy" range where the alloy is a combination of solid and liquid.

Figure 1: Silver-copper Equillibrium diagram

The temperature between solidus and liquidus is the melting range. As the temperature increases from solidus state moving toward liquidus state, melting and flow increase. The resulting sluggish flow can present challenges to capillarity when brazing joints.

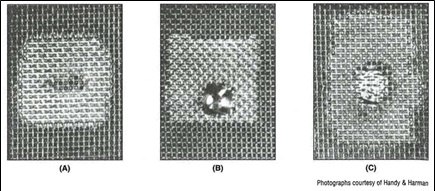

Filler metals that have wide melting ranges, some separation of the solid and liquid phases may occur. This is termed liquation: a partial melt of the lower ingredients in the filler metal, which in turn leaves a shell of the higher-melting material, called a skull. See Figure 2.

Figure 2: Liquation of AWS BAg-1 and AWS BAg-2 filler metals. (A) As a result of slow heating of AWS BAg-1 in a furnace, no liquation occurs with filler metals having a narrow melting range of 20°F (11°C). (B) As a result of slow heating of AWS BAg-2 in a furnace, a large skull remains due to liquation caused by the wide melting range of 70°F (39°C). (C) As a result of rapid heating of AWS BAg-2, a small skull remains.

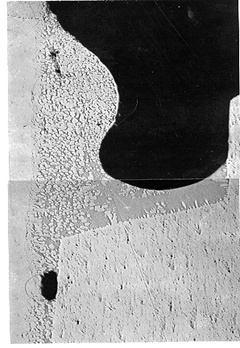

Liquation normally occurs during slow heating through the melting range of an alloy. Liquation may affect the integrity of a braze joint by potentially causing voids or a lack of adherence to base materials. See Figure 3.

Figure 3: AWS BCuP-5 used to braze parts in a two-hour furnace heating cycle. Braze joint shows evidence of Cu-rich (higher-melting constituent) area at upper left, as well as a void at bottom right-likely a consequence of liquation.

Figure 3: AWS BCuP-5 used to braze parts in a two-hour furnace heating cycle. Braze joint shows evidence of Cu-rich (higher-melting constituent) area at upper left, as well as a void at bottom right-likely a consequence of liquation.

In brazing, the base metal on a component should never be melted. Therefore, it is important to select a filler metal whose liquidus temperature is lower than the solidus temperature of both the base metals being joined. Several other factors should be considered prior to brazing-examples are listed as follows.

Examples

1. Brazing an assembly with a narrow clearance: Lucas-Milhaupt Silvaloy 560 is a cadmium-free alloy that begins to melt at 1145°F (620°C) and flows freely at 1205°F (650°C). Its melting range is 60°F (15°C).

2. Brazing an assembly with a wide clearance (greater than .005"/0.127mm): Lucas-Milhaupt Silvaloy 380 begins to melt at 1200°F (648°C) and is not completely molten until 1330°F (720°C). Alloys with a wide melting/flowing range are considered plastic and are useful for poor-fit conditions.

3. "Step brazing" an assembly: When brazing in the vicinity of a previously brazed joint, the second brazing must not disturb the first joint. The solution is to use more than one type of filler metal-a filler metal lower in liquidus temperature for the second joint than that used for the first joint. For an example in a stainless steel assembly which is step brazed could have Silvaloy 630, which melts and flows between 1275°F-1475°F (690°C-801°C), for the first joint and then Silvaloy 560 (1143°F-1205°F/618°C-651°C) for the second joint.

4. Assemblies that must be heat treated: (Option 1) heat treat and then braze-selecting a filler metal whose liquidus temperature is lower than the heat-treating temperature so the hardness will not be adversely affected by brazing, or (Option 2) heat treat and braze simultaneously-using a filler metal with a liquidus temperature closely equivalent to the heat-treating temperatures. Due to the complex nature of heat treat conditions of various base materials contact Lucas Milhaupt Technical Services for detailed information regarding your specific application.

CONCLUSION:

Liquidus is the lowest temperature at which an alloy is completely liquid; solidus is the highest temperature at which an alloy is completely solid. When choosing a filler metal for brazing applications, it is important to consider melting behavior-specifically liquidus temperature.

Lucas-Milhaupt is dedicated to providing expert information for Better Brazing. Please feel free to share this blog posting with associates. See Lucas-Milhaupt complete line of braze filler metals for your operation, and contact us if we may be of assistance.